Print: 29 Oct 2025

A budget on borrowed time

With no parliamentary fanfare, the interim government should present a cautious budget in a time of political flux – one that must do more than balance books; it must rebuild trust

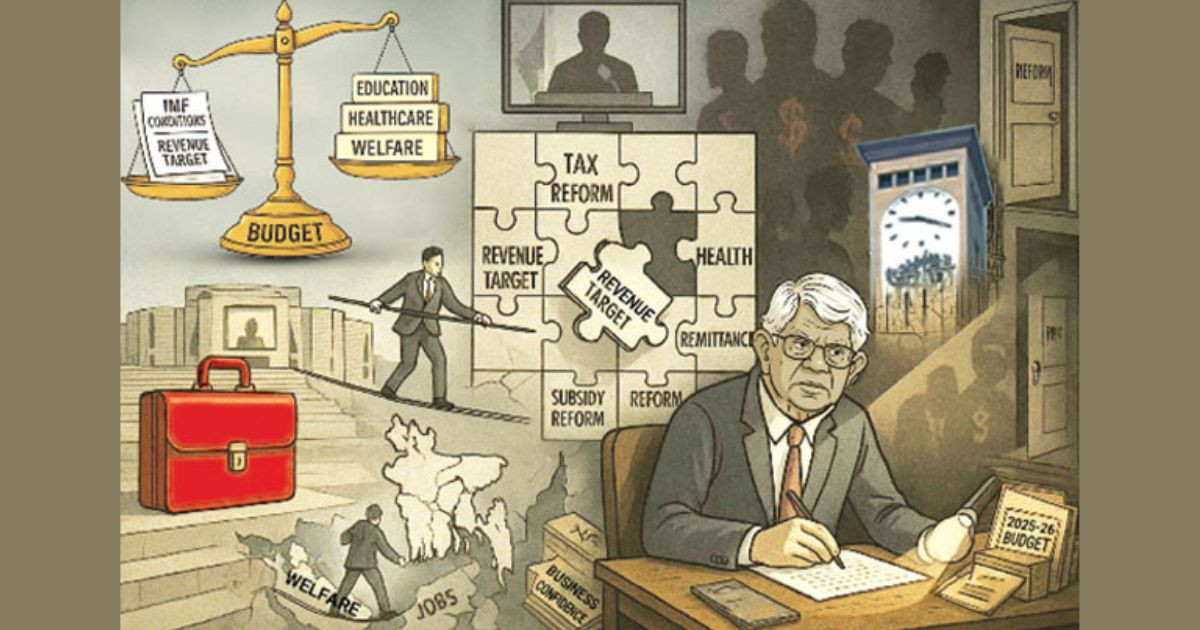

There will be no red briefcase this time. No finance minister striding up the steps of Parliament, no customary photo opportunity, no paper-waving inside the House. Instead, the national budget will be presented quietly, through a televised address by Dr Salehuddin Ahmed, the finance adviser to the interim government – more restrained than ceremonial, more cautious than celebratory. For many, it already feels different.

This is no ordinary budget day. It arrives under the watch of a non-political interim government, formed in the wake of a historic student-led uprising that saw the fall of the long-standing authoritarian Awami League regime. That wave of public discontent was rooted in frustration over economic mismanagement, corruption, and eroding accountability. The new administration came in riding that momentum, promising a fresh start – particularly in how the state manages public finance, governance, and institutional reform.

But with promises come expectations, and in this case, they are as high as they are fraught. Undeniably, this is the first real opportunity for the new administration to outline how it intends to steer the country away from the economic turbulence of recent years. But with that opportunity comes a critical question: does the government truly have the tools – or indeed the mandate – to introduce anything beyond the cosmetic?

Between crisis management and reform

To be clear, expectations of sweeping reform should be tempered. This is, after all, a non-elected government operating within a limited window, without a formal development manifesto or a long-term electoral mandate. Its scope for deep structural overhaul is naturally constrained.

What we are likely to see is a budget shaped more by immediate repair work than visionary reimagination. The focus will, understandably, be on stabilising inflation, taming the fiscal deficit, and meeting the bare minimum of IMF conditions. In that sense, it is more of a fire-fighting budget than a blueprint for transformation.

And yet, there is pressure to signal change – both to international lenders and to a weary public still reeling from inflation shocks and job insecurity. This dual audience puts the government in a difficult position: it must appear reformist without shaking the boat much.

At the same time, there is a growing sense of unease in the business community. Confidence is faltering, not just because of economic headwinds, but due to broader political uncertainty and a worsening law and order situation. Business owners and investors are increasingly hesitant – unsure of the rules, anxious about enforcement, and wary of becoming entangled in a system that often feels arbitrary. Without a clear signal that stability and fairness are returning, even the most well-crafted budget risks falling flat where it matters most: on the ground.

Lofty targets, leaky foundations

The most telling sign of this tension lies in the budget’s revenue target. The government is reportedly aiming to collect over Tk5.64 lakh crore in revenue – an ambitious figure under any circumstances, let alone in an economy still grappling with near double-digit inflation and subdued private sector activity.

Here is where the doubts begin to crystallise. For years, Bangladesh has struggled to expand its direct tax base. Fewer than three million people file returns in a country of 170 million. Much of the tax burden continues to fall on indirect sources – VAT, duties, excise – which are easier to collect but far more regressive in effect. Without bold measures to widen the direct tax net, the entire revenue strategy risks being aspirational at best, inflationary at worst.

As Dr Zahid Hussain, former lead economist of the World Bank’s Dhaka office, notes, “Achieving Tk5 lakh crore or more in revenue collection is very difficult – there is no precedent for that… If the goal is to increase revenue without increasing the public burden, then tax evasion must be addressed.”

It is a clear signal that the current revenue ambition may be structurally out of sync with what is practically achievable

What makes the situation even more concerning is that the budget appears to offer no concrete pathway for recovering defaulted loans or repatriating illicit money siphoned out of the country – two potential revenue sources that could ease pressure on the public without imposing new taxes.

Despite repeated calls for reforms such as property taxation, wealth and inheritance taxes, or even meaningful automation of income tax administration, progress remains minimal. The political will to confront powerful vested interests – those who benefit from loopholes and lax enforcement – still appears in short supply.

Indeed, many observers believe this year’s budget will be “predictable and conventional”, lacking any surprise measures to address long-standing leakages, such as poor loan recovery and rampant capital flight.

And so, one is left to wonder: if the same old machinery is being used, how realistic is it to expect a different outcome?

Cuts where it hurts

While social protection is expected to receive a modest boost – especially for the elderly, marginalised communities, and tea garden workers – there are worrying signs elsewhere. Reports suggest that both health and education could face significant cuts under the Annual Development Programme. This, in a country already spending less than 2% of GDP on each, is a troubling signal.

Education and healthcare are not just service sectors – they are the foundations of future productivity and resilience. Slashing them in the name of fiscal discipline sends a contradictory message. It undermines long-term growth while doing little to address short-term hardship.

Towfiqul Islam Khan, senior research fellow of the Centre for Policy Dialogue, underscores this trade-off, stating, “It is not just about how much the government spends, but how and where the money is allocated. Strategic prioritisation of expenditure is essential to ensure that limited resources are directed towards the most impactful sectors.”

More worryingly, it suggests that even amid crisis, the budget’s core assumptions remain tilted towards hard infrastructure over human capital.

It is difficult to reconcile that with the rhetoric of inclusive recovery.

Welfare, symbolism, and sustainability

One of the more visible features of this year’s budget is likely to be the inclusion of a sizeable allocation for victims of last year’s political violence. On the surface, this is a welcome and humane gesture – an attempt to provide restitution, medical care, and even skills training to those caught in the crossfire of history.

But even here, the question of sustainability arises. Can the state afford generous social welfare expansion while also servicing rising public debt, maintaining subsidies, and chasing aggressive revenue targets? Without a corresponding increase in direct tax collection or serious rationalisation of expenditure elsewhere, these commitments risk becoming symbolic rather than structural.

Moreover, there is little indication that the social protection strategy has been revisited in any meaningful way. The fragmented, often politicised nature of programme delivery remains a concern, as does the lack of a unified digital registry to prevent leakage and duplication.

Treading the IMF tightrope

Of course, no discussion of this budget is complete without acknowledging the elephant in the room – the IMF. The government is under pressure to show that it is serious about reform. That means reducing fiscal deficits, rationalising subsidies, and digitising tax administration. In theory, these are all laudable goals. In practice, they are politically and administratively messy.

What is worrying is that the path of least resistance – raising VAT rates, increasing fees, cutting back on development spending – is the one most likely to be taken. These measures are easier to implement quickly and look good on spreadsheets. But they disproportionately affect the poor and middle classes and do little to shift the economy away from its longstanding structural weaknesses.

Reform, in other words, is not just about ticking IMF boxes. It is about building legitimacy and capability at home. And that requires more than compliance – it requires conviction.

The missing conversation

Perhaps the most glaring absence in the lead-up to the budget has been public dialogue. There has been little effort to engage citizens, businesses, or civil society in shaping the fiscal agenda. That silence matters. Budgets, after all, are more than financial statements – they are moral and political documents. They signal who gets what, and why.

In times of uncertainty, dialogue becomes even more crucial. It helps manage expectations, build trust, and create a sense of shared ownership over difficult trade-offs. Unfortunately, that space for open conversation remains narrow.

Planting the seeds of credibility

None of this is to suggest that the current government can, or should, attempt sweeping overhauls overnight. But even within the limitations of an interim setup, there are credible ways to lay the groundwork for meaningful change. One of the clearest would be to focus on rebuilding trust – both among citizens and within the business community. And that starts with clarity. A publicly communicated roadmap outlining how reforms might be sequenced – even if deferred to the next elected government – would go a long way in signalling intent.

Taxation, too, could benefit from this kind of symbolic yet strategic thinking. Instead of relying on VAT hikes that hit lower-income groups the hardest, the government could introduce transparency tools – such as publishing anonymised tax data, piloting wealth declarations for top officials, or digitising asset disclosures. These are modest steps, but they send a strong message: that reform begins at the top.

On the spending side, small shifts in priority could speak volumes. Even modest reallocations away from politically favoured infrastructure projects towards basic health and education – particularly at the community level – would reflect a tilt towards inclusive development. Safeguarding school meal programmes or expanding primary healthcare access will not fix everything, but they would ease pressure on the most vulnerable and build longer-term resilience.

“Structure is more important than size,” reminds Towfiqul Islam Khan. “Restoring discipline in the economic sector is the principal challenge.” The implication is clear: a smaller, more targeted budget can be more effective than a sprawling one built on unrealistic assumptions.

Finally, there is an urgent need to bring people back into the budget conversation. Creating space for engagement – whether through digital platforms, regional dialogues, or civil society forums – can rebuild some of the trust that years of exclusion and opacity have eroded. In uncertain times, listening is not a luxury. It is a stabiliser.

A budget of limits

What, then, should we reasonably expect?

Not miracles, certainly. If this budget manages to avoid major policy missteps, maintain basic economic stability, and provide some immediate relief to the most vulnerable, it will have done a service. If it can signal even a faint move towards reform – tax digitisation, better targeting of subsidies, or reallocation away from white-elephant projects – that would be a modest but welcome step.

But let us not pretend this is a turning point just yet. For all the talk of change, the scaffolding remains largely the same. The tax structure is still narrow and unfair. Expenditure priorities remain questionable. And the space for democratic scrutiny is still limited.

There are also lingering concerns that a significant share of development spending – reportedly as high as 40% – may still be tied to inflated or mismanaged projects inherited from the past. This kind of fiscal leakage only deepens public scepticism.

Dr Zahid Hussain has called attention to the same concern, “Although it is being described as a reduced budget, the comparison is being made with last year’s budget, which itself was unrealistic… I had expected this year’s budget to be one of limited indulgence, focused on human development and pro-poor measures.” Instead, what is emerging looks ambitious on paper, but detached from the ground reality.

Of course, much of this remains speculative. The actual budget has not yet been placed, and it is entirely possible the government surprises us – with bolder moves or deeper concessions than anticipated. What we’re responding to here is the broader landscape: the political conditions, economic pressures, and institutional constraints within which the budget is being shaped. If the government chooses to rise above expectations – even in small, deliberate ways – it could shift the tone of public discourse and plant the seeds of something more lasting.

In the end, it is not the ambition of the numbers that will define this budget, but the integrity of its choices. And that is what the nation will be watching for.

A budget on borrowed time

With no parliamentary fanfare, the interim government should present a cautious budget in a time of political flux – one that must do more than balance books; it must rebuild trust

There will be no red briefcase this time. No finance minister striding up the steps of Parliament, no customary photo opportunity, no paper-waving inside the House. Instead, the national budget will be presented quietly, through a televised address by Dr Salehuddin Ahmed, the finance adviser to the interim government – more restrained than ceremonial, more cautious than celebratory. For many, it already feels different.

This is no ordinary budget day. It arrives under the watch of a non-political interim government, formed in the wake of a historic student-led uprising that saw the fall of the long-standing authoritarian Awami League regime. That wave of public discontent was rooted in frustration over economic mismanagement, corruption, and eroding accountability. The new administration came in riding that momentum, promising a fresh start – particularly in how the state manages public finance, governance, and institutional reform.

But with promises come expectations, and in this case, they are as high as they are fraught. Undeniably, this is the first real opportunity for the new administration to outline how it intends to steer the country away from the economic turbulence of recent years. But with that opportunity comes a critical question: does the government truly have the tools – or indeed the mandate – to introduce anything beyond the cosmetic?

Between crisis management and reform

To be clear, expectations of sweeping reform should be tempered. This is, after all, a non-elected government operating within a limited window, without a formal development manifesto or a long-term electoral mandate. Its scope for deep structural overhaul is naturally constrained.

What we are likely to see is a budget shaped more by immediate repair work than visionary reimagination. The focus will, understandably, be on stabilising inflation, taming the fiscal deficit, and meeting the bare minimum of IMF conditions. In that sense, it is more of a fire-fighting budget than a blueprint for transformation.

And yet, there is pressure to signal change – both to international lenders and to a weary public still reeling from inflation shocks and job insecurity. This dual audience puts the government in a difficult position: it must appear reformist without shaking the boat much.

At the same time, there is a growing sense of unease in the business community. Confidence is faltering, not just because of economic headwinds, but due to broader political uncertainty and a worsening law and order situation. Business owners and investors are increasingly hesitant – unsure of the rules, anxious about enforcement, and wary of becoming entangled in a system that often feels arbitrary. Without a clear signal that stability and fairness are returning, even the most well-crafted budget risks falling flat where it matters most: on the ground.

Lofty targets, leaky foundations

The most telling sign of this tension lies in the budget’s revenue target. The government is reportedly aiming to collect over Tk5.64 lakh crore in revenue – an ambitious figure under any circumstances, let alone in an economy still grappling with near double-digit inflation and subdued private sector activity.

Here is where the doubts begin to crystallise. For years, Bangladesh has struggled to expand its direct tax base. Fewer than three million people file returns in a country of 170 million. Much of the tax burden continues to fall on indirect sources – VAT, duties, excise – which are easier to collect but far more regressive in effect. Without bold measures to widen the direct tax net, the entire revenue strategy risks being aspirational at best, inflationary at worst.

As Dr Zahid Hussain, former lead economist of the World Bank’s Dhaka office, notes, “Achieving Tk5 lakh crore or more in revenue collection is very difficult – there is no precedent for that… If the goal is to increase revenue without increasing the public burden, then tax evasion must be addressed.”

It is a clear signal that the current revenue ambition may be structurally out of sync with what is practically achievable

What makes the situation even more concerning is that the budget appears to offer no concrete pathway for recovering defaulted loans or repatriating illicit money siphoned out of the country – two potential revenue sources that could ease pressure on the public without imposing new taxes.

Despite repeated calls for reforms such as property taxation, wealth and inheritance taxes, or even meaningful automation of income tax administration, progress remains minimal. The political will to confront powerful vested interests – those who benefit from loopholes and lax enforcement – still appears in short supply.

Indeed, many observers believe this year’s budget will be “predictable and conventional”, lacking any surprise measures to address long-standing leakages, such as poor loan recovery and rampant capital flight.

And so, one is left to wonder: if the same old machinery is being used, how realistic is it to expect a different outcome?

Cuts where it hurts

While social protection is expected to receive a modest boost – especially for the elderly, marginalised communities, and tea garden workers – there are worrying signs elsewhere. Reports suggest that both health and education could face significant cuts under the Annual Development Programme. This, in a country already spending less than 2% of GDP on each, is a troubling signal.

Education and healthcare are not just service sectors – they are the foundations of future productivity and resilience. Slashing them in the name of fiscal discipline sends a contradictory message. It undermines long-term growth while doing little to address short-term hardship.

Towfiqul Islam Khan, senior research fellow of the Centre for Policy Dialogue, underscores this trade-off, stating, “It is not just about how much the government spends, but how and where the money is allocated. Strategic prioritisation of expenditure is essential to ensure that limited resources are directed towards the most impactful sectors.”

More worryingly, it suggests that even amid crisis, the budget’s core assumptions remain tilted towards hard infrastructure over human capital.

It is difficult to reconcile that with the rhetoric of inclusive recovery.

Welfare, symbolism, and sustainability

One of the more visible features of this year’s budget is likely to be the inclusion of a sizeable allocation for victims of last year’s political violence. On the surface, this is a welcome and humane gesture – an attempt to provide restitution, medical care, and even skills training to those caught in the crossfire of history.

But even here, the question of sustainability arises. Can the state afford generous social welfare expansion while also servicing rising public debt, maintaining subsidies, and chasing aggressive revenue targets? Without a corresponding increase in direct tax collection or serious rationalisation of expenditure elsewhere, these commitments risk becoming symbolic rather than structural.

Moreover, there is little indication that the social protection strategy has been revisited in any meaningful way. The fragmented, often politicised nature of programme delivery remains a concern, as does the lack of a unified digital registry to prevent leakage and duplication.

Treading the IMF tightrope

Of course, no discussion of this budget is complete without acknowledging the elephant in the room – the IMF. The government is under pressure to show that it is serious about reform. That means reducing fiscal deficits, rationalising subsidies, and digitising tax administration. In theory, these are all laudable goals. In practice, they are politically and administratively messy.

What is worrying is that the path of least resistance – raising VAT rates, increasing fees, cutting back on development spending – is the one most likely to be taken. These measures are easier to implement quickly and look good on spreadsheets. But they disproportionately affect the poor and middle classes and do little to shift the economy away from its longstanding structural weaknesses.

Reform, in other words, is not just about ticking IMF boxes. It is about building legitimacy and capability at home. And that requires more than compliance – it requires conviction.

The missing conversation

Perhaps the most glaring absence in the lead-up to the budget has been public dialogue. There has been little effort to engage citizens, businesses, or civil society in shaping the fiscal agenda. That silence matters. Budgets, after all, are more than financial statements – they are moral and political documents. They signal who gets what, and why.

In times of uncertainty, dialogue becomes even more crucial. It helps manage expectations, build trust, and create a sense of shared ownership over difficult trade-offs. Unfortunately, that space for open conversation remains narrow.

Planting the seeds of credibility

None of this is to suggest that the current government can, or should, attempt sweeping overhauls overnight. But even within the limitations of an interim setup, there are credible ways to lay the groundwork for meaningful change. One of the clearest would be to focus on rebuilding trust – both among citizens and within the business community. And that starts with clarity. A publicly communicated roadmap outlining how reforms might be sequenced – even if deferred to the next elected government – would go a long way in signalling intent.

Taxation, too, could benefit from this kind of symbolic yet strategic thinking. Instead of relying on VAT hikes that hit lower-income groups the hardest, the government could introduce transparency tools – such as publishing anonymised tax data, piloting wealth declarations for top officials, or digitising asset disclosures. These are modest steps, but they send a strong message: that reform begins at the top.

On the spending side, small shifts in priority could speak volumes. Even modest reallocations away from politically favoured infrastructure projects towards basic health and education – particularly at the community level – would reflect a tilt towards inclusive development. Safeguarding school meal programmes or expanding primary healthcare access will not fix everything, but they would ease pressure on the most vulnerable and build longer-term resilience.

“Structure is more important than size,” reminds Towfiqul Islam Khan. “Restoring discipline in the economic sector is the principal challenge.” The implication is clear: a smaller, more targeted budget can be more effective than a sprawling one built on unrealistic assumptions.

Finally, there is an urgent need to bring people back into the budget conversation. Creating space for engagement – whether through digital platforms, regional dialogues, or civil society forums – can rebuild some of the trust that years of exclusion and opacity have eroded. In uncertain times, listening is not a luxury. It is a stabiliser.

A budget of limits

What, then, should we reasonably expect?

Not miracles, certainly. If this budget manages to avoid major policy missteps, maintain basic economic stability, and provide some immediate relief to the most vulnerable, it will have done a service. If it can signal even a faint move towards reform – tax digitisation, better targeting of subsidies, or reallocation away from white-elephant projects – that would be a modest but welcome step.

But let us not pretend this is a turning point just yet. For all the talk of change, the scaffolding remains largely the same. The tax structure is still narrow and unfair. Expenditure priorities remain questionable. And the space for democratic scrutiny is still limited.

There are also lingering concerns that a significant share of development spending – reportedly as high as 40% – may still be tied to inflated or mismanaged projects inherited from the past. This kind of fiscal leakage only deepens public scepticism.

Dr Zahid Hussain has called attention to the same concern, “Although it is being described as a reduced budget, the comparison is being made with last year’s budget, which itself was unrealistic… I had expected this year’s budget to be one of limited indulgence, focused on human development and pro-poor measures.” Instead, what is emerging looks ambitious on paper, but detached from the ground reality.

Of course, much of this remains speculative. The actual budget has not yet been placed, and it is entirely possible the government surprises us – with bolder moves or deeper concessions than anticipated. What we’re responding to here is the broader landscape: the political conditions, economic pressures, and institutional constraints within which the budget is being shaped. If the government chooses to rise above expectations – even in small, deliberate ways – it could shift the tone of public discourse and plant the seeds of something more lasting.

In the end, it is not the ambition of the numbers that will define this budget, but the integrity of its choices. And that is what the nation will be watching for.